Traveling by night and following the North Star to freedom, groups of African Americans took a zigzag route to avoid slave catchers and would “wade through the water” to throw hunting dogs off their scent.

They threw hush puppies – small pieces of cornmeal – on the ground to distract the animals and keep them quiet when the former slaves got close.

“Thus the term ‘hush puppies,'” said Deborah Richardson Price, executive director of the Underground Railroad Museum of Burlington County, during a tour last month.

Despite the dangers of being caught and perhaps killed, the heartbeat of freedom pushed the formerly enslaved people north through Maryland and Delaware by land and sea.

Eating what they could find, sleeping in the woods and using a mild opiate to keep children from crying, the African Americans looked for quilt codes on the windows of supportive abolitionists telling them to pack up and go or that a body of water was nearby and boats were waiting, Price explained.

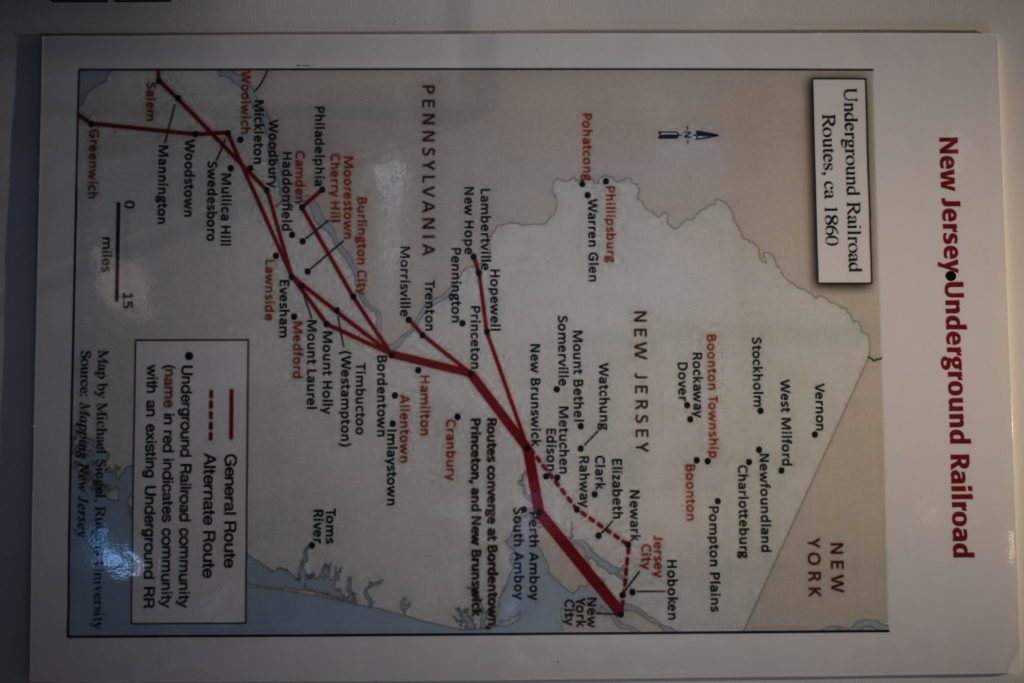

They would cross the Delaware Bay concealed in the holds of the cargo sailboats owned and operated by free Blacks, and would head to Greenwich or Salem and continue north to a series of safe houses in Woodstown, Mullica Hill, Woolwich, Haddonfield, Lawnside, Evesham, Medford and Mount Laurel.

Another route on the Underground Railroad took people who had escaped from southern plantations and made it safely to Philadelphia up the Delaware River to Burlington Island by boat. Along the way, they were able to rest and eat a good meal at safe houses in Palmyra, Riverton, Beverly and Burlington City.

Others went up the Rancocas Creek to Timbuctoo, a free Black village in Westampton, while receiving help from abolitionists and Quakers in Moorestown and Mount Holly who opposed slavery.

New Jersey was a major artery of the Underground Railroad, taking some of the freedom seekers up to Newark, into New York City, and eventually to Canada when the Fugitive Slave Act – which required slaves be returned to owners – was enacted in 1850, Price noted.

The Underground Railroad Museum tour on the grounds of Smithville Historical Park in Eastampton begins with lithographs of African people in the 17th century being captured and forced into a life of slavery. They were overloaded into the cargo holds of ships headed to the Americas, according to Price.

“Many of them died on the voyage,” she said.

Another museum room depicts the brutal and demeaning life of enslaved people, treated as commodities by their masters and whipped in public if they disobeyed. One particularly disturbing display case showed how slaves were shackled and tortured, branding irons used to identify them, cat-o-nine tails used to whip them, a ball and chain weighing 40 pounds to prevent escape, cattle prods used to move them, and neck shackles and chains with an advertisement etched into the metal from a company that specialized in “tobacco and n……”

“I only say that (n) word once during the tour,” Price acknowledged. “It is so degrading.”

“The Underground Railroad was a collaboration between African Americans, abolitionists, Quakers, the indigenous community and churches,” Price pointed out. Sympathetic pastors and ministers would burn crosses on the floors of their churches to provide air ducts for the freedom seekers hiding in the basement.

One room in the tour featured the most well-known Underground Railroad conductor, Harriet Tubman, who escaped slavery alone from a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland. She was 27 and eventually made it to William Still’s law office in Philadelphia.

A fearless woman, Tubman made 13 more trips back to Maryland with a bounty on her head and led 76 people – including family members – to freedom. A master of disguise known as Moses, Tubman would sing “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” while approaching the people she was going to take on the perilous road to freedom and “the promised land.”

In her own words, “I was a conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say. I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

Price then led museum visitors to the Civil War room, featuring African American soldiers who fought with the Union Army, including the first female soldier, Cathay Williams, who disguised herself as a man. The room also highlighted the first woman to lead a major military operation in America – Harriet Tubman – still fighting for the freedom of her people.

She and 150 African American Union soldiers sailed down the Combahee River in South Carolina and conducted a raid at Combahee Ferry. They rescued 727 enslaved people, who came running from the plantation to the boats in a breathtaking dash to freedom.

Visitors receive a pamphlet from the pleasant Denise Love as they walk in the door describing the museum’s mission:

“The Underground Railroad Museum of Burlington County is dedicated to keeping history alive, connecting the past to the present through the acquisition and presentation of historic artifacts and materials, while giving voice to history through creative expression in art, music and the spoken word.”

Open every Saturday and Sunday from noon to 4 p.m., the museum operated in Burlington City for several years as a private enterprise by Louise Calloway, at a site directly behind a station on the Underground Railroad, Wheatley’s Pharmacy.

Following the museum’s closure in the spring of 2013, county commissioners decided to exhibit the facility’s possessions at Smithville. The museum is an independent organization, separate from the county parks system. This year, the board of commissioners awarded a grant of $20,000 to support the museum’s African Diaspora Festival and other activities.

Among activities that Price is excited about is an upcoming bus tour on Friday, Dec. 29, that will take 54 people to 12 sites throughout Burlington and Camden counties associated with the Underground Railroad, including the Peter Mott House in Lawnside and Quaker Friends Meeting houses.

“There will be special guests on the bus ride, and the individual curators will talk about the history of each site,” Price said.

For information or to join the tour, call (609) 914-1675 or go to www.hugrrmbc.org.